A test for the waterproof-yness of a waterproof membrane. Is the waterproof membrane actually waterproof? Seems like a completely fair question to me. Well funny enough, in NZS 4858, our current method for testing for this, the membrane doesn’t have to be waterproof. You don’t even have to test if it resists water. I’ll say it one more time, in cool quotes:

Waterproof membranes are not required to be waterproof according to our NZ Standard 4858

Let me explain.

Firstly, and I want to make this as clear as possible:

NZS4858 is listed exactly nowhere in the building code as an acceptable test method for determining waterproof nature of a membrane.

It doesn’t appear in E2, it doesn’t appear in E3. There is literally no legal or quasi legal or scientific justification for using this test. It’s then entirely unclear to me how this test is being applied and relied on as demonstration of building code compliance. That is a made up link between a test and building code compliance using ‘that’s the way we’ve always done it’ and ‘it’s been working’ as supporting evidence.

No, it really hasn’t, it’s been failing, like a lot, as described herein.

There is a common set of tests to figure out how fast water goes through a material. It was originally made for the food industry to make sure packaged foods didn’t dry out on the shelves and we then stole it to tell us if our walls would or wouldn’t go mouldy (spoiler alert, they will). This set of tests is ASTM E96 – universally applied all over the planet. Put a membrane between two air/water spaces and measure how fast water goes through them. How do you measure? You just weigh them every so often and graph the trend. There are three ways to test and you’d select the one most relevant to your situation. And they always, always, (well maybe not always, it’s the same if it’s 0) give you a different result depending on which method you choose:

- Dry Cup Method (Procedure A) – One side is 0% RH, the other side is 50%

- Wet Cup Method – (Procedure B) – One side is 50% RH, the other side is 100%

- Inverted Wet Cup (Procedure BW) – One side has water against the membrane, the other side is 50% RH

If you were a wet area membrane, which of the above would you be expected to pass? Which is the most relevant things to test?

- Procedure A has almost no relevance to construction materials. Never going to have 0% RH. Interesting but not useful.

- Procedure B, complete and total relevance. This is the situation where water gets in and needs to dry back out (that how walls work/don’t work)

- Procedure BW looks an awful lot like a roof, dunnit? Water on the roof, and a bit of humidity inside.

You can guess where this is going. Instead of testing BW, the geniuses at standards NZ (I’m sure there were more than one, and I’m sure all lovely people, and not all from standards) thought Procedure A was the right one and now we all test membranes to a condition without any relevance to construction.

And they don’t even have to be 0 g/ sqm/day, you can have up to 8 g/sqm/day!

“What if it’s above 8, Shawn?”

Well don’t you worry because even that might be ok. I can’t make this up: if you can’t resist 8g/sqm/day, under completely fictitious laboratory conditions, then what you need to prove is that a sheet of particleboard won’t swell up too much to rupture the membrane. This is the moisture absorption test and you can have up to 10% increase in moisture content in just 24 hours! What about the 15-50 years the membrane is supposed to last? What if I have some really kickass particle board that doesn’t absorb water very fast?

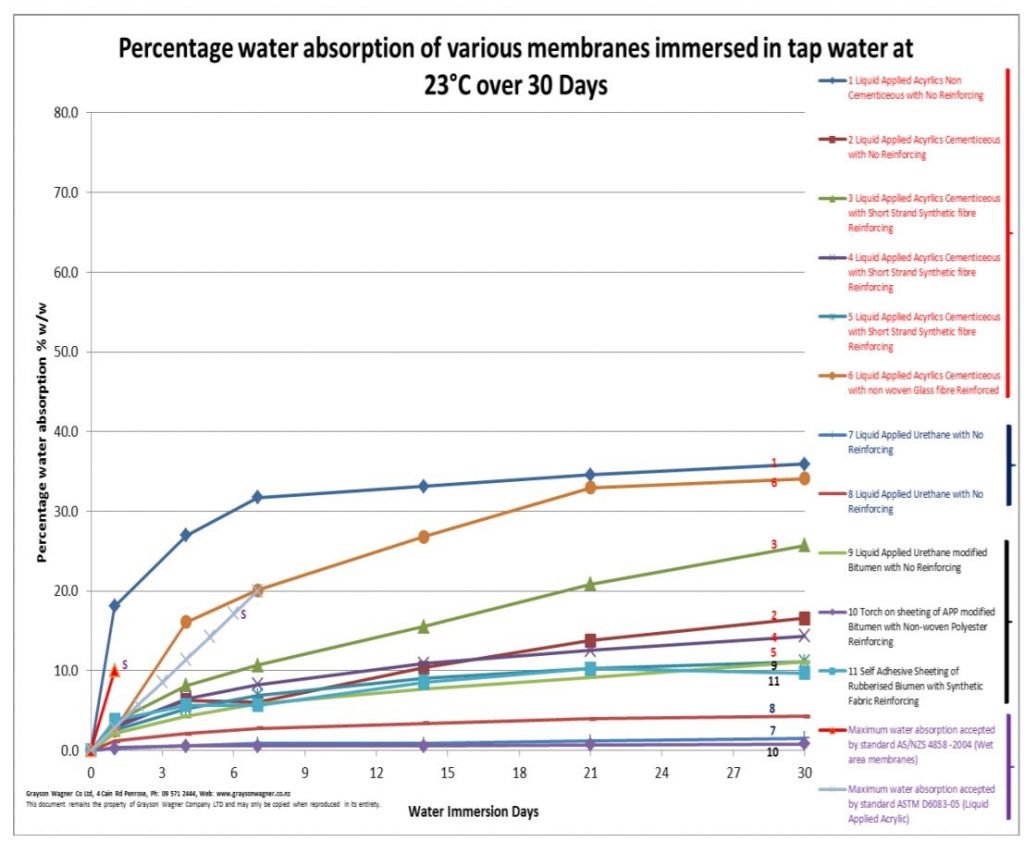

Absorbing water into a membrane is just as bad or maybe worse. The part above measures whether water goes through it, but roof membranes acting as sponges isn’t a good look either. There are reams and reams of standards used to verify the water absorption rates which are acceptable for different membranes. Some can do ok with some absorption, others can’t. Many of these tests are done in less than a week, but as Grayson Wagner (GW)(see report below) comments, it’s the long term absorption that is important and interesting to us. Maybe something like 30 days is enough to show a trend, GW did this testing and 30 days at 23C looks about right (note many of these membranes are widely used all across New Zealand still to this day, they still meet the ‘Standard’ and carry appraisals and Codemark certificates)(and yes, they are the ones you are specifying, without a doubt):

Hmmm, some didn’t do so well. 20% absorption in 3 days is not waterproof.

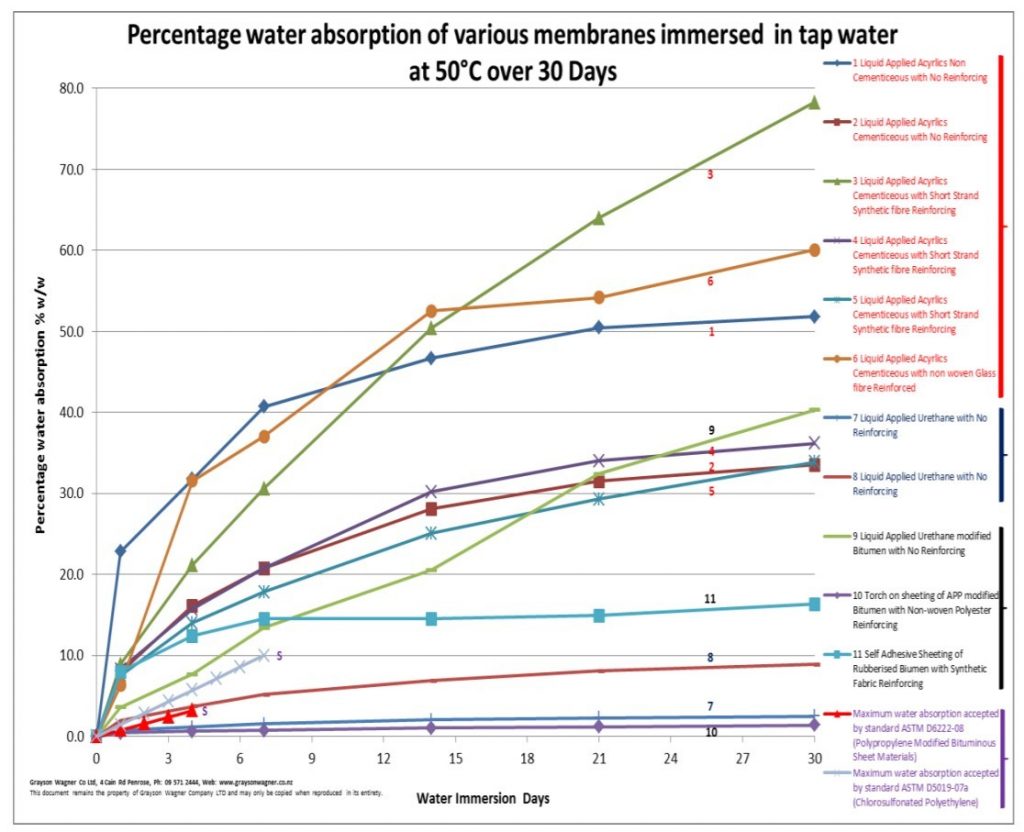

So when you want to test the longer term performance of something in a really short time, you add heat. That adds energy to the system and makes molecular things happen quicker. GW did the same sample of membranes, this time at 50C and WTF is going on?!

Which is more likely:

- The ASTM absorption criteria (developed by chemists, scientist, manufacturers, reviewed constantly in a country like the US where you get sued so hard if you’re wrong) is overly conservative on the absorption crtieria

- We ballsed it up in NZ and went with the NZ scientific method of ‘She’ll be Right”

These semi-permeable roof membranes are a well known and documented failure mode for membranes: https://www.rdh.com/blog/osmotic-blistering-bane-liquid-applied-waterproofing-membranes/

“But that hasn’t happened in NZ”

Uh, yeah it has, a whole lot, and these guys told everyone about it for the past 10 years and no one has been listening: https://graysonwagner.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/NZIA-membrane-paper-website-copy-pdf2.pdf.

What should we be testing for instead?

- Long term moisture absorption rate. Something realistically long like 30 days at 50C maybe and then the trendline at 30 days must be (or very near) 0g/sqm/day. A touch more than our current 24 hours.

- ASTM E96 – Wet Cup (BW) to be very near (effectively 0g/sqm/day. Completely different than a Dry Cup test.

The combination of those two is how you determine if something is waterproof. Let me be perfectly clear:

if you are providing and expert opinion on the building code compliance of a waterproofing membrane and you are relying on NZS 4858, that is negligence in the first order.

So when your statement is (hypothetically) ‘Test methods and results have been reviewed by [us] and found to be satisfactory’, that’s going to be hard to defend later when it all goes wrong (and it already has).